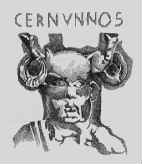

Cernunnos was worshipped by the iron age Celts all across Europe as late as the first century AD, and his worship must have begun centuries before that.

The Celts had no written language of their own, and although their druids could write in Latin and Greek they were forbidden to write down any of their knowledge. The classical writers themselves never mentioned this particular Celtic divinity, and so we have nothing in writing about him at all. Everything we know about him can only be guessed at from the iconography: the images of him created by the Celts themselves.

The Celts

made numerous models, or icons, of their various gods, and there are over 60

depicting Cernunnos, from all over Europe. We only know his name because it is

carved on a single one of these, made by sailors from the Gallic Parisii tribe

(from whom Paris got its name) in the first century AD, by which time Gaul

(modern France) had become a Roman province. The earliest image of him that has

been found was carved on rock in Northern Italy in the 4th century BC. We do not

know how widespread the use of this exact name was: it is possible that this was

the name for this antlered god to no-one but the Parisii themselves, but the

structure of the name suggests otherwise.

The Celts

made numerous models, or icons, of their various gods, and there are over 60

depicting Cernunnos, from all over Europe. We only know his name because it is

carved on a single one of these, made by sailors from the Gallic Parisii tribe

(from whom Paris got its name) in the first century AD, by which time Gaul

(modern France) had become a Roman province. The earliest image of him that has

been found was carved on rock in Northern Italy in the 4th century BC. We do not

know how widespread the use of this exact name was: it is possible that this was

the name for this antlered god to no-one but the Parisii themselves, but the

structure of the name suggests otherwise.

Cornu in modern French means "horned, because modern French has grown from the Latin language imposed upon them by the Romans. The Latin for horn is also cornu. The Romans had a habit of changing local names to fit the Roman pattern: most Roman names end in us. So Cernunnos is a Roman name meaning Horned One. It was probably the new Romanised name given by the Gauls to all their very old horned gods, in which case its use may have been widespread through out Gaul after it became a Roman province.

The images

of him are unusually consistent. His main attribute are his horns, those of a

stag. He is usually portrayed as a mature man with long hair and a beard. He

wears a torc: this was an ornate neck-ring worn by the Celts to denote nobility.

He often carries other torcs in his hands or hanging from his horns.

The images

of him are unusually consistent. His main attribute are his horns, those of a

stag. He is usually portrayed as a mature man with long hair and a beard. He

wears a torc: this was an ornate neck-ring worn by the Celts to denote nobility.

He often carries other torcs in his hands or hanging from his horns.

He is usually portrayed seated and cross-legged, in the meditative or shamanic position.

Cernunnos is nearly always portrayed with animals, in particular the stag. He is also frequently associated with a unique beast that seems to belong only to him: a serpent with the horns of a ram. Less often he is associated with other beasts, including bulls, dogs and rats.

The ram-horned serpent is particularly interesting. The serpent occurs in myths all across the world, and is nearly always associated with knowledge. Usually these associations are purely pagan, but remember that it was a serpent that tempted Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge. It is also commonly associated with death and the otherworld, and is hence described as cthonic. Cernunnos carries it in his left hand, and in his right he carries a torc, the Celtic symbol of nobility, the symbol of having been initiated into that special state.

Was Cernunnos the Celtic god of initiation ?

I am a stag of seven tines,

I am a wide flood on a plain,

I am a wind

on the deep waters,

I am a shining tear of the sun,

I am a hawk on a

cliff,

I am fair among flowers,

I am a god who sets the head afire with

smoke.

I am a battle waging spear,

I am a salmon in the pool,

I am a

hill of poetry,

I am a ruthless boar,

I am a threatening noise of the

sea,

I am a wave of the sea,

Who but I knows the secrets of the unhewn

dolmen ?

Origin obscure but certainly Celtic

Because of his frequent association with beasts he is often referred to as The Lord of the Animals. Because of his association with stags in particular (a particularly hunted beast) he is also known as The Lord of the Hunt.

The Stag Lord, The Horned God of the Hunt, The Lord of the Forest...of all the Celtic divinities (with the exception of Danu) none has caught the imagination of modern pagans so much as Old Horny himself.

The most detailed, clear and famous of all images of Cernunnos comes from a unique and marvellous piece of Celtic work: The Gundestrup Cauldron.

Cauldrons had magical significance for the Celts, and this is the most ornate ever found. It was beaten out of 10 kg of silver, probably in the second century BC, constructed from 13 heavily decorated rectangular panels and a plain bowl containing a 14th circular one (possibly a late addition). The entire assembly is 70 cm in diameter.

Sometime around the birth of Christ it was taken to pieces and apparently just left on the ground in a bog near what is now the hamlet of Gundestrup in Northern Jutland, where it gradually became overgrown and covered with peat. It remained there until its discovery by peat cutters in 1891.

The eight external panels (of which one is missing) each feature what appears to be the single face of a different god or goddess, surrounded by much smaller humanoids or beasts. The five interior panels each depict many characters, men, women, gods and beasts, in what may be a story.

One of these panels depicts Cernunnos.

He is seated cross-legged. He has antlers with seven tines (or points per horn), and is, unusually, depicted clean-shaven. He wears a torque and carries a second one in his right hand. He wears a tunic and bracae (Celtic trousers) which cover him from the wrist to above the knee, and a patterned belt. He wears sandals on his feet. His hair appears to be brushed straight back.

In his left hand he holds the ram-horned serpent. This serpent also appears on another two of the five interior panels.

Surrounding him are many beasts. The nearest, on the left, almost touching horns with him, is a stag, itself of seven tines, indicating his special affinity with this beast. Close to him on the right is a dog. There are also two horned animals that may be ibexes, three long-tailed animals that could be lions, and a boy on a fish. The space between the beasts is decorated with a simple pattern of vegetation.

The five internal panels are complex, and feature many characters who may be gods, goddesses or heroes. All of these characters seem to appear also on one of the eight external panels, with the exception of Cernunnos, who clearly does not. Did his image appear on the lost eighth external panel ?

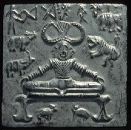

The

origins of the Celts are obscure, but it has been suggested that they lie far to

the East around the Indo-European Plateau. If so, we should not be so surprised

to find ancient gods there who might be cousins of our own local horned deity.

This ancient image came from Mohenjo Daro, in the North-West of modern India on

the River Indus, and is believed to have been made around 2,000 BC. It is

thought to be the seated figure of a very early version of

Pashupati, the Lord of the Animals in Hindu mythology,

peacefully surrounded by his beasts.

The

origins of the Celts are obscure, but it has been suggested that they lie far to

the East around the Indo-European Plateau. If so, we should not be so surprised

to find ancient gods there who might be cousins of our own local horned deity.

This ancient image came from Mohenjo Daro, in the North-West of modern India on

the River Indus, and is believed to have been made around 2,000 BC. It is

thought to be the seated figure of a very early version of

Pashupati, the Lord of the Animals in Hindu mythology,

peacefully surrounded by his beasts.

The resemblance is striking.

"The Gods of the Celts" by Miranda Green (Alan Sutton Publishing ISBN 0-86299-292-3)

"Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend" by Miranda Green (Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-01516-3)

"Animals in Celtic Life and Myth" by Miranda Green (Routledge, ISBN 0-415-05030-8

"The Horned God" by John Rowan (Routledge and Kegan Paul)